Work and value

Kim Trogal

When describing or defining what resilience is, one thing descriptions consistently seem to miss is, what makes resilience? Systems might be described in terms of their characteristics, for example, having ‘redundancy’ (some slack in them); being ‘flexible,’ and ‘polycentric;’ enabling ‘learning and experimentation’ for example.1Biggs, R, et al (2012). Toward Principles for Enhancing the Resilience of Ecosystem Services, Annual Review of Environment and Resources 37, pp. 421–448. These defining characteristics, emerging from eco-systems science, are helpful in identifying resilience in various fields. But my question is what makes resilience? Who and what creates and maintains ‘redundancy,’ or flexibility in a particular system, for instance, and in what kind of conditions?

In the introduction to E P Thompson’s seminal book The Making of the English Working Class historian Michael Kenny asks:

‘What happened to the working class Thompson describes? […] Where are the habits of self-reliance, the sense of solidarity and common purpose, the willingness to defend rights based on customary English inheritance, and the toil and craft that were central to ethos of the class he depicts? When exactly did the English working class get unmade?’2Kenny, M (2013). Introduction to E P Thompson, The Making of the English Working Class, London, Penguin Books, p. viii. [My Emphasis].

Or, put differently, what unmade this particular ‘culture of resilience’?

Whilst the reasons are complex, one factor amongst them was the emerging dominance of the commodity logic. Following Polanyi’s account of the same period, he describes its increasing application to a number and type of relations, fundamentally to ‘Land, Labour and Money.’3Polanyi, K (2001). The Great Transformation: The Political and Economic Origins of Our Time, 2nd Beacon Paperback edition, Boston, MA: Beacon Press. This type of relation now applies variously to seeds, genetic material, digital coding, ideas, language, knowledge, medicines, culture and more, today.

‘My question is what makes resilience? Who and what creates and maintains “redundancy,” or flexibility in a particular system, for instance, and in what kind of conditions?’

Thinking back to the question, ‘what makes resilience’, there is a difficulty. As a number of the other contributors here indicate, resilience requires a different set of values (commons, collaboration, generosity, care, reciprocity) rather than the ones of the commodity, for instance. Thinking about ‘what makes resilience,’ one of the significant commodified relations that needs to be addressed then, must be work. It takes work to make a community, to create ‘slack’ (think for instance, of the ‘old fashioned’ larder, building a stock of reserves), the work to foster experimentation, to enable learning, to maintain a network, to care for others, to share, to negotiate. What makes resilience is work, and as such it is bound up with ‘the problem of work,’ to borrow Kathi Weeks’ expression. Namely, the dominance of waged work as the prime and privileged form of activity.4Weeks, K (2011). The Problem with Work, Feminism, Marxism, Antiwork and Postwork Imaginaries, Durham and London: Duke University Press.

The ‘problem with work’ (amongst other things), is that it excludes all the human and non-human activities that make life, and in our interest here, resilience. The work that sustains life is work that frequently exists on the edges of, outside of, or otherwise exploited by our dominant economy. This work might include subsistence production, volunteering, mutual aid through time-based currencies, community gardening, food cooperatives, the sharing and management of local resources from parks, pastures to local libraries, tool banks, local initiatives, online shared resources, open data, open software.

Initiatives like these (and more of course) rely on different economies and often different kinds of contributions to sustain them. There are different kinds of exchanges, donations, not least the ‘gift of time.’ The economies these initiatives bring is apparent to, and valued by, those involved, not least because gifts and donations can bring significance and meanings. For example, when time and effort is given out of desire or ‘goodwill’ rather than ‘because one is paid to’ – there is a qualitative difference in both the relations and the meaning a project or object takes on. But the idea, that one should work ‘out of love’ for symbolic rewards, rather than monetary ones is complex.

Whilst these economies are visible and tangible to those participating, a problem from my perspective is that this kind of work, particularly in local, civic contexts, is invoked and held up as exemplar by proponents of a ‘big society’. This uncomfortable co-incidence is one of a number when working with resilience. For example: a de-centralised, networked system, with ‘diversity’ and ‘slack’ whilst characteristic of a resilient system, is equally compatible with a neoliberal approach to work. This is evident for example in increased outsourcing, the increased use of self-employment (transferring employer’s responsibilities to staff themselves), or zero-hour contracts where the burden of ‘redundancy’ in a system is transferred to individuals. Equally, for example, the other side of flexibility is precarity.

‘It takes work to make a community, to create “slack” … the work to foster experimentation, to enable learning, to maintain a network, to care for others, to share, to negotiate.’

What could bring a more self-determined nature or control into this situation? How to choose the ‘slack’ for instance, rather than being subjected to it? I am interested in how to understand the nature of such a choice, in a time of semiotic capitalism; where and how is desire produced and what is it directed towards? Carrotworkers Collective (now the precarious workers brigade), use the image of the donkey chasing the carrot on a stick, as a metaphor for precarious work and unpaid internships in the cultural industries. They not only critique this condition, but point to the need for more sophisticated understandings of the affective conditions in which we ‘work for free.’ The carrot, represents the hopes and desires produced within us. The carrot is the things we care for, but is at the same time ‘the false promise.’5Zechner, M (2010). Seminar 14: Protest and Propose: Pressing Conversations Around Research and Action. http://linesofflight.wordpress.com/2010/11/26/protest-and-propose-pressing-conversations-around-research-and-action/. See also http://carrotworkers.wordpress.com and http://precariousworkersbrigade.tumblr.com

If we know that developing our resilience is essential if we are to survive turbulent futures, my question is how, through the tools of art, design and spatial practice, can we deal with its political ambiguity in respect to the work and activities that actually make it? This involves both the material and financial conditions as well as the affective and symbolic economies in which the work is situated. Given that design contributes to the production of particular kinds of material economies and desire, through advertising, imagery, products, aesthetics and so on, could it not also help to create and sustain different value chains, in different economic relations?

There might be many ways to think about these questions, but I am interested in a few in particular:

- How to deploy the tools of ‘diverse economies,’ in order that we can perform and embed different kinds of economies in our everyday lives and work? These are tools, generously given to us by Katherine Gibson, Julie Graham and their many colleagues,6Gibson-Graham, J K, Cameron, J & Healy, S (2013). Take Back the Economy: An ethical guide to transforming our communities, Minneapolis, London, University of Minnesota Press. Gibson-Graham, J K (2006). A Postcapitalist Politics, Minneapolis, London, University of Minnesota Press. to help us identify the diversity of economies around us. Their tools aim to help us as individuals and groups elaborate different kinds of markets (capitalist, alternative, informal and so on), different forms of labour and so on. Their suggestion is that by articulating these diverse economies and making them visible, we can make more conscious decisions about the kinds of economies we want to support and participate in. Whilst the tools have been developed in the context of regional development, they could well be deployed in any field, in any place. How to make use of them in our fields, work and everyday lives?

- How might the skills of art, design and spatial practice help us work better with the more ‘invisible’ labours and relations, the things normally ‘beyond measure’? Given the affective and symbolic aspects of cultural production, could they not also actively engage in, and support different kinds of values? Producing and sustaining new symbolic economies? And,

- How to better connect with social and spatial justice movements, and other political movements, through the work that we do?

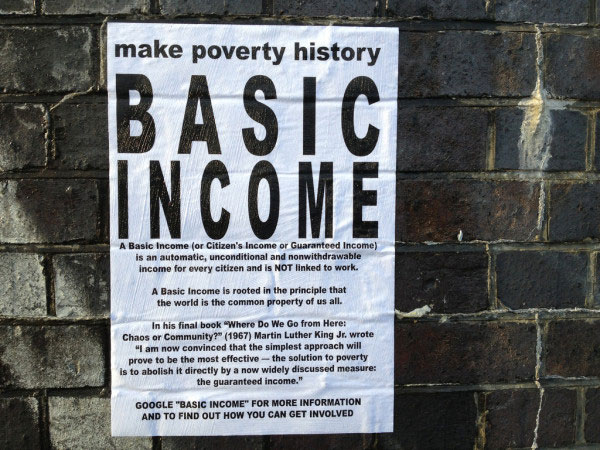

In relation to the ‘problem of work’ Kathi Weeks, argues for a demand to a basic income. More recently, journalists polled readers on ideas around a citizen’s income or basic income, a minimum income guarantee separated from work.7Should a citizens’ income replace the benefits system?, Survey in The Guardian, Monday 11th August 2014. See also: http://www.basicincome.org A culture of resilience should (I think) be engaging in debates like these and, directing work towards their realization.

References

| 1. | ↑ | Biggs, R, et al (2012). Toward Principles for Enhancing the Resilience of Ecosystem Services, Annual Review of Environment and Resources 37, pp. 421–448. |

| 2. | ↑ | Kenny, M (2013). Introduction to E P Thompson, The Making of the English Working Class, London, Penguin Books, p. viii. [My Emphasis]. |

| 3. | ↑ | Polanyi, K (2001). The Great Transformation: The Political and Economic Origins of Our Time, 2nd Beacon Paperback edition, Boston, MA: Beacon Press. |

| 4. | ↑ | Weeks, K (2011). The Problem with Work, Feminism, Marxism, Antiwork and Postwork Imaginaries, Durham and London: Duke University Press. |

| 5. | ↑ | Zechner, M (2010). Seminar 14: Protest and Propose: Pressing Conversations Around Research and Action. http://linesofflight.wordpress.com/2010/11/26/protest-and-propose-pressing-conversations-around-research-and-action/. See also http://carrotworkers.wordpress.com and http://precariousworkersbrigade.tumblr.com |

| 6. | ↑ | Gibson-Graham, J K, Cameron, J & Healy, S (2013). Take Back the Economy: An ethical guide to transforming our communities, Minneapolis, London, University of Minnesota Press. Gibson-Graham, J K (2006). A Postcapitalist Politics, Minneapolis, London, University of Minnesota Press. |

| 7. | ↑ | Should a citizens’ income replace the benefits system?, Survey in The Guardian, Monday 11th August 2014. See also: http://www.basicincome.org |