EXPLORING THE POTENTIAL FOR SOCIAL ENGAGEMENT WITHIN PRODUCT DESIGN CURRICULA

JANE PENTY

This reflection focuses on some key insights from participant feedback that has led to a re-assessment of my views on the pros and cons of socially motivated community collaborations embedded in the curriculum for product designers. Ezio Manzini’s Cultures of Resilience project came at a good moment, spurring me to examine and challenge the reservations that I discuss here. So when some connections with local organisations came my way, we explored what a collaboration with the BA Product Design course might look like with the following caveats:

- responding to the brief would at least in part lead to a product design outcome

- the short timescale we have available would lead to design concepts, not development or implementation.

The result of these discussions were two projects, Lets Sort it Out (LSiO) with Camden Environmental Services facilitated by Central Saint Martins’ (CSM) Public Collaboration Lab and the Living Lab with the Calthorpe Project and Communities by Design, both outlined below.

Coincidentally, both projects dealt with transforming our relationship with waste although they were tackled from very different perspectives. LSiO was about how product designs can facilitate behaviour change for residents on council estates to increase recycling. The Calthorpe Living Lab addresses waste by demonstrating to visitors their closed-loop urban food cycle: growing on site, consuming in the café and digesting this and other waste to feed new growing. Providing a cohesive message and finding ways to engage visitors through all the possible touch points was the main objective.

While both projects applied a human centred design approach, their structure was quite different. LSiO was fully facilitated with co-discovery and co-design workshops thanks to the Public Collaboration Lab, but personal relationships were more difficult to negotiate, whereas at Calthorpe, students were able to embed themselves in site activities through volunteering and engaging in more ad-hoc conversation with visitors. Many of the students involved in Calthorpe have said that they will continue their involvement by either implementating of their projects or volunteering and helping out in others ways.

Reviewing feedback from students and the different stakeholders, the first common outcome is that all those involved became highly sensitised to the issues around waste. While this is not an earth shattering finding it is important to remember that exposure to an issue is the first step in transformation. Therefore, in this type of project, the number of people involved (quantity) as well as the nature of the encounters created (quality) directly affect its impact.

For the rest, rather than trying to sum up and analyse, I will let some of the participants’ own words speak for themselves.

STUDENT FEEDBACK

THE BEST THING ABOUT THIS COMMUNITY LOCATED DESIGN PROJECT WAS…

Calthorpe:

- “the human involvement/interaction”

- “the open minded attitude of the people running the project”

- “building relationships with people and feeling that my designs can truly make an impact on their lives”

Camden:

- “grasping the complexity and making sense of all the inputs”

- “really valued getting feedback throughout the process”

- “the range of stakeholders we had access to”

THE MOST DIFFICULT/FRUSTRATING THING ABOUT THIS PROJECT WAS…

Calthorpe:

- “the short time frame in which a very complex problem needed to be solved.”

- “putting ideas forward without meaning any harm or hurting people as this is a project that is really close to them so it is hard to hear the negatives.”

- “simplifying, taking a step back from the complexity and focusing”

- “that you can’t solve everything and please everyone in a 5 week project”

Camden:

- “original fear: oh, another recycling project – another bin…”

- “seeing the reality on the ground, in peoples flats, can be limiting – getting past that”

- “encountered quite closed minds to new solutions – dealing with that was difficult”

- “disappointed with uptake by residents of sessions (talking to 5 people…), some were just there for the free Waitrose voucher”

- “the pressure and challenge of communicating to strangers who don’t know what Product Design is”

MY MOST MEMORABLE MOMENT IN THIS PROJECT WAS WHEN…

Calthorpe:

- “I volunteered - several times”

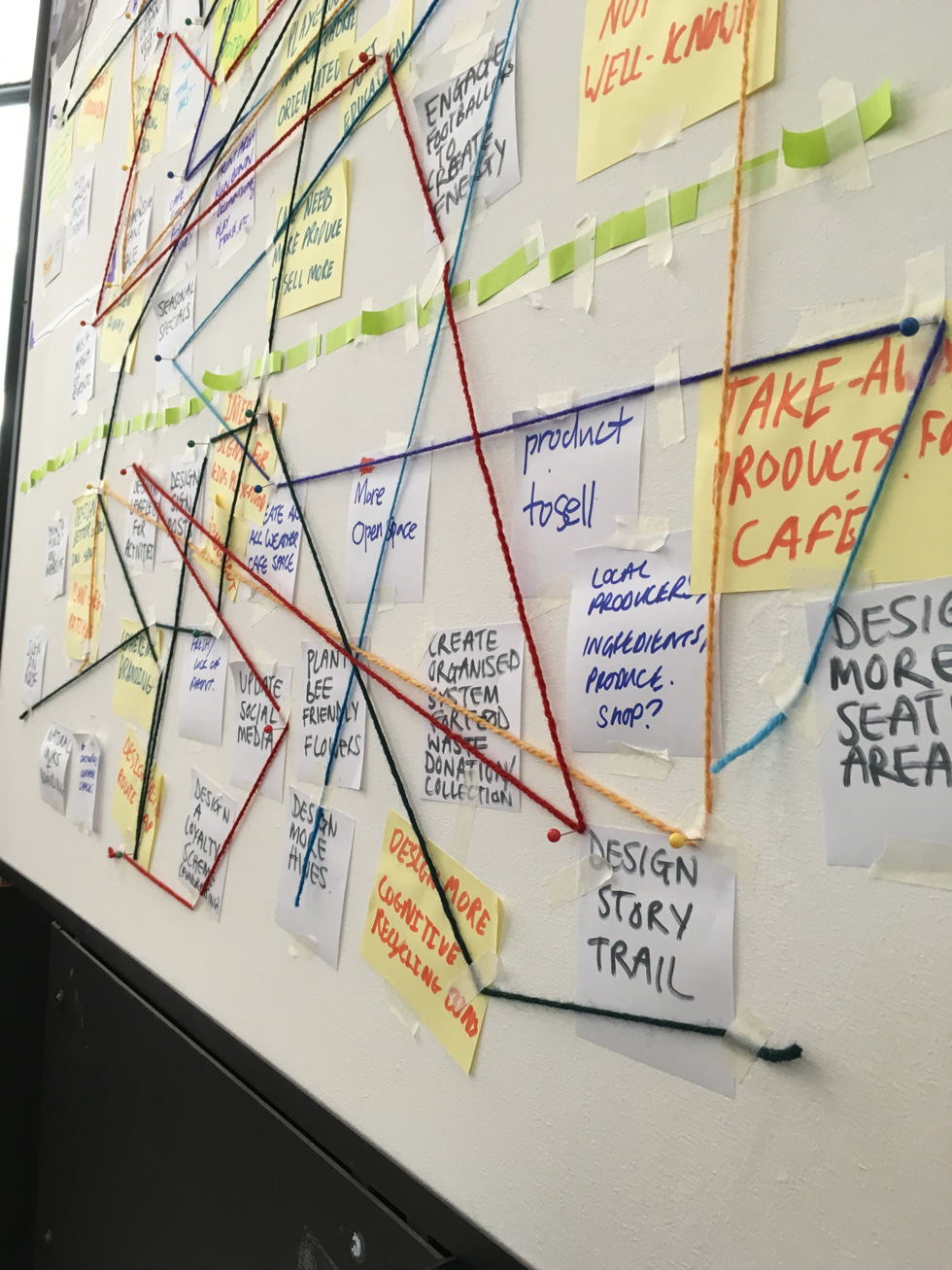

- “Calthorpe allowed our group to take over a room and hold a vibrant and energetic ideation session.”

- “I volunteered several times in the Café, I enjoyed helping out and felt a strong sense of belonging to Calthorpe.”

- “I propagated my own plants and starting hydroponics in my house, I took Calthorpe and it’s ethos home!”

Camden:

- “a resident showed us around their whole flat – they were very proud – [that is when] I understood their attitude to their space and their possessions.”

- “experimenting with ways to engage residents in the co-discovery and co-creation stages”

- “I realised that these designs could actually make a difference.”

OTHER STAKEHOLDER FEEDBACK

In order of comments: Calthorpe: project lead; Camden: resident and council officer.

DID YOU GAIN ANY UNIQUE INSIGHTS FROM THE EXPERIENCE?

Calthorpe

- “The process has certainly added value to the Calthorpe Living Lab project, giving us a multitude of fresh ideas, many of which seem implementable. To have young minds applying their creativity to a complex issue as individuals and in groups seems to help break it down into manageable pieces and the diversity of the offerings meant we now have developed ideas in many areas, which we can take further.”

Camden:

- “Nice to see all the different parties represented at the Presentation Day - it would be wonderful if Camden could arrange all interested parties in one room, for other issues!”

- “It was a great experience to see this platform that created conversation between real life (estate residents with a recycling/waste problem) and the interaction with the students that come with a fresh and creative approach to the problem. I think that made me see the value of bringing new ideas, new people and new perspective to my daily work.”

DO YOU THINK THAT THE RESIDENTS / COUNCIL HAVE OR WILL BENEFIT FROM THIS PROJECT – SHORT TERM? LONGER TERM? HOW?

Calthorpe:

- “They will benefit by having more entry points, which will make it easier to understand what the Calthorpe Living Lab is trying to achieve.”

Camden:

- “Funnily enough, I was thinking only this morning that it seemed as though that came and went and we will not benefit at all. I'm sad about that.”

- “I can see the benefit for the Council in the longer term. Because the next steps are to … see if there is any opportunities to develop some of the products and ideas that the students had.”

REFLECTION

Reflecting on this feedback confirms that everyone enjoys ‘fresh ideas’ and that there is much to be gained by students and tutors from this type of engagement. Overwhelmingly the students involved appreciated the facilitated access with ‘real people’ and the empathy, focus and meaning that specificity of place and people brings to their work. Although I would say that overall there is more benefit to students, in both projects, I see our partners also benefitting from the research insights and the possibilities that ‘fresh ideas’ open up mentally. In the case of Camden however there is a clear sense of frustration due to the limited scope for implementation.

Beyond creating possibility, taking any of these ideas through to development and implementation would seem to depend on the organisations’ own capacities and the complexity of their systems. In the case of LSiO, many of the solutions proposed, while valid with a holistic view of the problem, do not fall under the council remit, so the scope for taking them further is limited. For this type of project perhaps the biggest win is through a much higher resident engagement for sensitisation rather than direct product outcomes. Calthorpe on the other hand is a grassroots organisation largely made up of volunteers and community groups, and the technology for implementation is either one-off or batch production. This leaves the door open for the students to have continued engagement and for some of the projects to move forward through volunteering and crowd funding.

Taking the reflection more personally, not so very long ago, I questioned the correctness of involving design students in community projects that professed to deal with ‘social issues’ within the constraints of our academic curriculum. This might seem a strange position for someone who has been closely involved in a number of community action and campaigning groups over the last 30 years. But these were activities connected to my personal life and geographical community. In fact, my real ‘community’ grew out of these activities from the intense bonds of trust and regard that are created when people work together for a common cause.

It is also strange from someone who for the last twenty-five years in HE design education has led both small and big community academic collaborations. The difference is that these were primarily design-led projects, ranging from installations for arts festivals to the development of cyclestations for the London to Paris off-road cyclepath. The main difference is that although these interventions clearly had social benefits, we did not intentionally set out to solve ‘social issues’ or to create a sense of community and place.

And even stranger from someone with a deep conviction of the urgent need for change in our relationship with the planet and each other if we are to slow down its rapid impoverishment or sudden collapse.

But I digress and I would like to clarify my reservations. The thought of playing a do-gooding-academic setting things up for our (mostly privileged) students to pop in and out of people lives for a short time, ostensibly ‘solving problems’ or ‘benefitting the community’ simply made me shudder. Why? Because I could see most of the gain being on our side and possible frustration or loss of trust on the other.

Given that the whole nature of social problems is that they are on-going and systemic, the one ingredient they need is long-term commitment and follow-through. Both of these are hard for us to offer in any meaningful way within the constraints of our five to seven-week curriculum project windows. In summary, aside from the lack of extra resources that these projects require for facilitation and organisation compared with the other external projects we run, my biggest fears were the effects of short term, in-out involvement and lack of scope for follow-through and implementation.

So lots of reasons for sitting on my hands that these two projects have made me revisit.

Going forward, I would favour giving community embedded projects a regular place in our curriculum, rather than being ad hoc. This means that we as a course could cultivate on-going relationships with a small number of organisations that would understand both the limitations and benefits of what we can offer. At the same time, at an institutional level within CSM Public and the Socially Responsive Design and Innovation Unit, we should look to the models of other Universities such as Design Matters at Arts Centre and Pontifical Catholic University of Rio de Janeiro amongst many others, for ways and means to take our activities beyond the standard curriculum through to a more flexible model that will allow for greater continuity and support of development and implementation stages.