How design thinking and ‘maker spaces’ might foster communities in place for returning citizens

Lorraine Gamman and Adam Thorpe

“Let us suppose that an industrial designer or an entire design office were to ‘specialise’ exclusively within the areas of human needs …There would be the design of teaching aids… and devices for such specialised fields as adult education, the teaching of both knowledge and skills to the retarded, the disadvantaged, and the handicapped; as well as special language studies, vocational reeducation for the rehabilitation of prisoners…”

Victor Papanek, Design for The Real World, 1971, p73.

Why is it so difficult to change ineffective prison systems, many of which if not state funded at enormous cost by the tax payer, would simply go bankrupt and whose rising expenses are in danger of crippling nations? This paper will answer that question by arguing that a ‘people and place’ strategy, is often missing from prison reform proposals, but is central to tackling recidivism and preventing social disengagement that leads to crime. Three sections of this paper that follow will look at (i) prison facts in UK and global context (ii) exemplar/case studies in keeping with Papanek’s account of the need for “the rehabilitation of prisoners” (iii) “through the door” design led community based project proposals.

1. Prison Facts reveals that the high cost of prison and the criminal justice system to the UK tax payer is nearly as expensive as the entire national education budget1Prison Reform Trust, “Prison: the facts – Bromley Briefing Summer 2015, http://www.prisonreformtrust.org.uk/Portals/0/Documents/Prison%20the%20facts%20May%202015.pdf. Despite the massive failure of our prisons to make a difference, the UK continues to invest in this punitive system which keeps 90,000 people away from their families, communities and places that should be involved in helping them change. Prison time often punishes minor crimes, far removed from the communities who experienced them and who could be involved in discussing the aftermath, the events that led to their occurrence, or the steps that might be taken to ‘payback’ victims and try to make things right. Consequently, UK prisoners, with mental health or drug addiction problems2http://www.rcpsych.ac.uk/healthadvice/problemsdisorders/mentalillness,offending.aspx, rarely get opportunities to engage with restorative processes3See discussion of Restorative Process and participatory design in Gamman L and Thorpe A in Wolfgang J. et al (editors) Transformation Design: Perspectives of New Design Attitudes, Bird, 2015., or do not do so consistently. Unsurprisingly, many inmates experience anger and frustration, rather than ‘correction’. They are put in a cell, congealed in time with little rehabilitative input from prison, then released into communities, either as ticking ‘time bombs’ or frozen souls4Jose-Kampfner, C., “Coming to Terms with Existential Death: An Analysis of Women’s Adaptation to Life in Prison,” Social Justice, 17, 110 (1990) and, also, Sapsford, R., “Life Sentence Prisoners: Psychological Changes During Sentence,” British Journal of Criminology, 18, 162 (1978). Craig Haney, The Psychological Impact of Incarceration: Implications for Post-Prison Adjustment, December 2001., with few prospects for employment or resettlement. So almost 60%5http://open.justice.gov.uk/reoffending/prisons/ 59% reoffend within 12 months of returning citizens in the UK reoffend and return to prison within a year. When there are so many alternative systems to prison available6Discussion of alternatives to prison see: http://famm.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/08/FS-Alternatives-in-a-Nutshell-7.8.pdf, it does not make sense that in the global context nations continue to invest in mass incarceration, particularly when, in the majority of cases it does not work. Whilst it may deliver a form of state ‘revenge’ or retribution, it is rarely shown to reduce reoffending, improve civil society or solve crime problems. Both in the UK, and USA, the mass incarceration system, often housed in alienating archaic prison architecture (subject to significant design critique for its failings)7For broad discussion see B. Dreisinger 2016; for prison design see Y Jewkes, H Johnston –“the evolution of prison architecture, Handbook on Prisons, 2007. fails to equip the majority of returning citizens with anything like the positive life re-entry skills they need to succeed as returning citizens. Even if, as Baz Dreisinger (2016) points out this system does raise significant profits for some private companies.8Baz Dreisinger, Incarceration Nations, Other Press, New York, 2016. At a time when government calls for all things evidence based the justice system is a glaring anomaly. An evidence based justice system would not look like this.

2. Case Studies from Europe, however, show, from diverse research perspectives, that not all countries are as ineffective as Britain or the USA. Germany and the Netherlands9Ram Subramanian and Alison Shames Sentencing and Prison Practices in Germany and the Netherlands: Implications for the United States (Vera Institute of Justice, October 2013) Federal Sentencing Reporter Vol. 27, No. 1, Ideas from Abroad and Their Implementation at Home (October 2014), pp. 33-45 (Published by: University of California Press on behalf of the Vera Institute of Justice)., for example, have introduced numerous progressive penal system reforms. As have Norway perhaps the most well-regarded in Europe for their success in rehabilitating offenders, with only 20% recorded recidivism10James Erwin “The Norwegian prison where inmates are treated like people”, Guardian, February 23, 2013.. This may be because Norwegian prisons are kept small (rarely housing more than 50 people) to create supportive community environments that cultivate both restorative and rehabilitative relations and values. The Norwegian Support Model11The Norwegian Support Model is discussed at length by Dreisinger, 2016, pp 271-306. as it is known, connects inmates to the same welfare services as local people, inside and outside of jail. This means, unlike the UK where people get ‘lost’ in the anonymous prison system, a Norwegian inmate belongs to the same municipality ‘before’ and ‘after’ prison. This system is designed to resemble life outside as much as possible, so education, healthcare and other social services are provided by the same source inside and outside of prison. Family and community are kept close to the inmates too, because the systemic approach here is to embed restorative and healing processes into the prison system where possible, in order to get offenders to understand civil truths about why crime hurts their families and communities and ultimately does not really benefit anyone. So the voices of victims, notions about forgiveness and family relations very much matter to the way the criminal justice system is managed in Norway, all aimed at ultimately delivering Justice Reinvestment through prison. This approach, founded in regimes led at Bastoy Prison12http://www.bastoyfengsel.no/English/, and the latest flagship Halden Prison13See discussion of Haldon Prison in Thomas Ugelvik, Imprisoned on the Border: Subjects and Objects of the State in Two Norwegian Prisons, Justice and Security in the 21st century: Risks, Rights and the Rule of Law, Barbara Hudson and Synnøve Ugelvik (eds), Abingdon: Routledge, 2012. in Norway have been informed by many including Nils Christie14Nils Christie.Limits to Pain: the role of punishment in the penal policy, 1981 reprinted EugeneOR: Wipf and Stock, 2007., a respected Norwegian criminologist who made it his life’s work to argue for emptying prisons and restorative processes. Of course, even Christie recognized that seriously violent criminals should be locked up, but went on to point out that the justice system does a poor job of determining which criminals are so incorrigible that they need to stay behind bars, and this is the crux. It is not always clear. So the Norwegians invest not just in prisoners but in empathetic staff who know how to foster positive relations with inmates15To work in a Norwegian Prison staff must first obtain a special 2-year degree in criminology, law, ethics, applied welfare and social work, that promotes humanitarian values and relations, as well as delivering job satisfaction and status., unlike the Americans and the Brazillians who put great numbers of inmates in solitary confinement as a matter of course16Lisa Guenther Solitary Confinement: Social Death and its Afterlives, Minnapolis, University of Minesota Press, 2013..

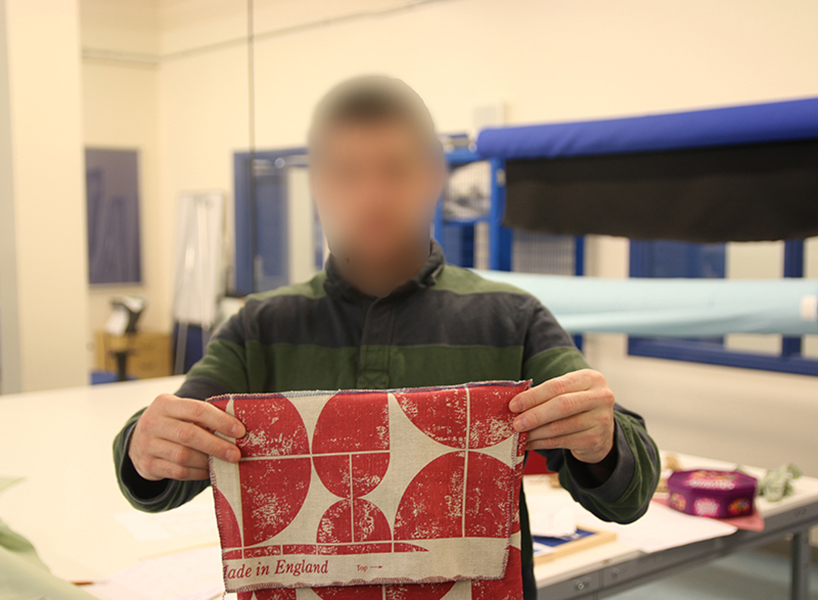

3. The Makeright – design thinking for prison industries17https://makerightorg.wordpress.com project understands change is a slow revolution. Operating at HMP Thameside, Plumstead led by the Design Against Crime Research Centre it seeks to connect education and prison industries, and to provide a positive reflective process for inmate learning18https://www.designweek.co.uk/new-scheme-launched-to-teach-design-thinking-to-prisoners/. The history of the project, is documented elsewhere, suffice it to say it took some time to get ‘buy in’ for the project from the necessary dutyholders but by 2015 the DACRC team had began training HMP Thameside inmates working in the textiles studios there, in design processes and methods. The focus of the design activity was the creation of a range of anti theft bags, co designed by inmates, to be sold in Sue Ryder charity shops in the UK. This ‘rags to bags’ project engages inmates in sustainable restorative processes. Using their knowledge and creativity inmates are trained and supported to design and manufacture bags from fabrics salvaged from damaged clothing donated to Sue Ryder shops. In this way inmates are able to pay something good back to society (the bags will generate income for Sue Ryder and protect people from crime). In designing and delivering design resources and teaching for inmates the Makeright project is a first iteration of a prison based design education programme that might move inmates towards reflective self knowledge, positive change and the finding of a ‘higher self’ more effectively than dour punishment ever could. It seems to work. In repeating the 8 week course several times, including students and other volunteers to work alongside us ‘facilitating’ inmates, our team have found that the participatory design process we implemented with inmates both in the UK (and at Sabarmati Jail with NID staff in India19http://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/city/ahmedabad/NID-goes-to-Sabarmati-jail-for-designs-against-theft/articleshow/51164067.cms) worked not only to generate bags but also to introduce opportunities for empathetic connection and encounters, reflection, discovery and self recognition that generative education usually brings. So much so that it provoked us to recognized that ‘hooks for change’20Giordano et al.’s (2002) suggests significance in terms of their theory of cognitive transformation; namely, ‘exposure to a particular hook or set of hooks for change’; Inspiring Change Scotland –http://www.artsevidence.org.uk/media/uploads/evaluation-downloads/mc-inspiring-change-april-2011.pdf that are argued to lead to desistance, were manifesting before our eyes. But also to realize that these ‘hooks’ need to become anchored to secure inmates on ‘a pathway to desistance’. The course and the certification process required by the prison is simply a beginning, but nowhere near enough to deliver desistance. We observed that some inmates who were inspired by the course, and said that they wanted to change, were seeking communities on the outside, engagement with whom might make good their desistance.

At the moment in the UK inmates like Lee (pictured) when they are paroled, are often banned from returning to the locations where their crime was committed in the first place, often near where their families live and so end up breaking the conditions of license and because of this return to prison. Another inmate told a member of HMP Thameside staff he twice broke conditions of his license on purpose because “he could not afford to finish the training he started in prison (it was £2000 to complete ‘outside’) so he went back ‘inside’ to get the bricklaying course certification”21Email conversation with HMP Thameside colleague on 11 May, 2015..

These ‘terms of licence’ are clearly an attempt to distance the returning citizen from the provocations that might lead to recidivism but often they do not operate effectively and serve to isolate vulnerable people from their support networks; also to alienate them in unfamiliar communities where they do not have easy access to education of other opportunities. This unworkable scenario appears to set the cost of desistance as isolation and alienation. Even the prison community does not let them return, within six months, without reoffending, nor on leaving offer very much support, other than usual probation services, to inmates as returning citizens.

In response to this scenario, and building on the observed positive changes engagement in design and making can deliver, we are currently seeking funding, supported by National Offender Management and Fab Lab London, to combine education in digital design and manufacture with our existing design education activities, so as to create an education programme that can be delivered in prison (within newly installed maker spaces) and/or within Fab Labs/Maker spaces local to participating prisons, on day release. The Fab Lab network (www.fabfoundation.org) and other open manufacture spaces is a creative community. Maker culture is known for its focus on collaboration, on sharing knowledge, through group activities with making, and for introducing mutual support systems. Fab Labs ethos of ‘make, learn, share’ / ‘learn, make, share’ speaks of their open inclusive and collaborative approach top innovation, which places emphasis on self-sufficiency and enterprise. Inmates who are trained in design and maker cultures (of resilience) first inside then on day release, will be well prepared to enter these mutually supportive communities on release. We want to work with Fab Lab because of their strong track record in delivering teaching and training to a wide range of learners from young children to company directors. We believe that collaboration between NOMS, Fab Lab London and ourselves can find ways to enrich life experiences and harness entrepreneurial potential and well as empathetic encounters, for those who leave prison without a job waiting for them, and without a community to provide a place. It is an experiment we haven’t yet begun but which we are encouraged by research findings to push forward as the next designed move. Demos (2016), identify that “a ‘people and place’ strategy is central to tackling isolation, and that redesigning cities… could help prevent social disengagement”22http://www.demos.co.uk/press-release/designing-housing-to-build-companionship/. We extend Demos’ account about the needs of the ageing population to also include those returning from prison (and perhaps other marginalized and vulnerable groups). Perhaps the two communities have complimentary needs that could be explored by social innovation designers in the future?23Getting men trained to be carers may require a real intellectual leap by some prisons – as it is about “soft” training compared to “manly” tasks like plastering, fork lift or truck driving. The backdrop is that in the UK labour aristocracy and the models of masculinities that go with it have been challenged in the post war period. Just like every where else, working class male pride in a manly job well done has few outlets and may now transforms, according to Grayson Perry, into physical demonstration of “hardness” through martial arts and subculture… See: http://www.theguardian.com/tv-and-radio/2016/may/05/grayson-perry-all-man-martial-arts-durham-miners-suicide-masculinity. We have observed that in HMP Thameside prison gym is no.1 pursued activity and sewing takes a leap of faith.

Conclusion

We believe that designing spaces inside and outside prison to foster development of the skills and mindset reentry from prison back to wider society requires is what is needed to address the problem of recidivism. That understanding people and place should be central to the conception and realization of strategies for releasing prisoners as ‘returning citizens’. And, there are precedents for this approach. The John Jay University founded in New York, offers college courses and reentry programs to incarcerated men throughout New York State who are interested in academic education24http://johnjayresearch.org/pri/projects/nys-prison-to-college-pipeline/. The scheme increases access to higher education for individuals during, and importantly, directly after prison – using the University as a community asset able to provide opportunities for inmates to successfully reintegrate. We believe such community assets, places and spaces (such as Fab Labs) come in different shapes and sizes. We need also to accommodate inmates who may not be academic but are creative and/or entrepreneurial and need new opportunities, with new communities, to support their reentry to society and avoid the revolving door of the prison system.

References

| 1. | ↑ | Prison Reform Trust, “Prison: the facts – Bromley Briefing Summer 2015, http://www.prisonreformtrust.org.uk/Portals/0/Documents/Prison%20the%20facts%20May%202015.pdf |

| 2. | ↑ | http://www.rcpsych.ac.uk/healthadvice/problemsdisorders/mentalillness,offending.aspx |

| 3. | ↑ | See discussion of Restorative Process and participatory design in Gamman L and Thorpe A in Wolfgang J. et al (editors) Transformation Design: Perspectives of New Design Attitudes, Bird, 2015. |

| 4. | ↑ | Jose-Kampfner, C., “Coming to Terms with Existential Death: An Analysis of Women’s Adaptation to Life in Prison,” Social Justice, 17, 110 (1990) and, also, Sapsford, R., “Life Sentence Prisoners: Psychological Changes During Sentence,” British Journal of Criminology, 18, 162 (1978). Craig Haney, The Psychological Impact of Incarceration: Implications for Post-Prison Adjustment, December 2001. |

| 5. | ↑ | http://open.justice.gov.uk/reoffending/prisons/ 59% reoffend within 12 months |

| 6. | ↑ | Discussion of alternatives to prison see: http://famm.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/08/FS-Alternatives-in-a-Nutshell-7.8.pdf |

| 7. | ↑ | For broad discussion see B. Dreisinger 2016; for prison design see Y Jewkes, H Johnston –“the evolution of prison architecture, Handbook on Prisons, 2007. |

| 8. | ↑ | Baz Dreisinger, Incarceration Nations, Other Press, New York, 2016. |

| 9. | ↑ | Ram Subramanian and Alison Shames Sentencing and Prison Practices in Germany and the Netherlands: Implications for the United States (Vera Institute of Justice, October 2013) Federal Sentencing Reporter Vol. 27, No. 1, Ideas from Abroad and Their Implementation at Home (October 2014), pp. 33-45 (Published by: University of California Press on behalf of the Vera Institute of Justice). |

| 10. | ↑ | James Erwin “The Norwegian prison where inmates are treated like people”, Guardian, February 23, 2013. |

| 11. | ↑ | The Norwegian Support Model is discussed at length by Dreisinger, 2016, pp 271-306. |

| 12. | ↑ | http://www.bastoyfengsel.no/English/ |

| 13. | ↑ | See discussion of Haldon Prison in Thomas Ugelvik, Imprisoned on the Border: Subjects and Objects of the State in Two Norwegian Prisons, Justice and Security in the 21st century: Risks, Rights and the Rule of Law, Barbara Hudson and Synnøve Ugelvik (eds), Abingdon: Routledge, 2012. |

| 14. | ↑ | Nils Christie.Limits to Pain: the role of punishment in the penal policy, 1981 reprinted EugeneOR: Wipf and Stock, 2007. |

| 15. | ↑ | To work in a Norwegian Prison staff must first obtain a special 2-year degree in criminology, law, ethics, applied welfare and social work, that promotes humanitarian values and relations, as well as delivering job satisfaction and status. |

| 16. | ↑ | Lisa Guenther Solitary Confinement: Social Death and its Afterlives, Minnapolis, University of Minesota Press, 2013. |

| 17. | ↑ | https://makerightorg.wordpress.com |

| 18. | ↑ | https://www.designweek.co.uk/new-scheme-launched-to-teach-design-thinking-to-prisoners/ |

| 19. | ↑ | http://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/city/ahmedabad/NID-goes-to-Sabarmati-jail-for-designs-against-theft/articleshow/51164067.cms |

| 20. | ↑ | Giordano et al.’s (2002) suggests significance in terms of their theory of cognitive transformation; namely, ‘exposure to a particular hook or set of hooks for change’; Inspiring Change Scotland –http://www.artsevidence.org.uk/media/uploads/evaluation-downloads/mc-inspiring-change-april-2011.pdf |

| 21. | ↑ | Email conversation with HMP Thameside colleague on 11 May, 2015. |

| 22. | ↑ | http://www.demos.co.uk/press-release/designing-housing-to-build-companionship/ |

| 23. | ↑ | Getting men trained to be carers may require a real intellectual leap by some prisons – as it is about “soft” training compared to “manly” tasks like plastering, fork lift or truck driving. The backdrop is that in the UK labour aristocracy and the models of masculinities that go with it have been challenged in the post war period. Just like every where else, working class male pride in a manly job well done has few outlets and may now transforms, according to Grayson Perry, into physical demonstration of “hardness” through martial arts and subculture… See: http://www.theguardian.com/tv-and-radio/2016/may/05/grayson-perry-all-man-martial-arts-durham-miners-suicide-masculinity. We have observed that in HMP Thameside prison gym is no.1 pursued activity and sewing takes a leap of faith. |

| 24. | ↑ | http://johnjayresearch.org/pri/projects/nys-prison-to-college-pipeline/ |