How fashion’s habits and locations shape our cultures and contribute to authorship of our lives

Dilys Williams

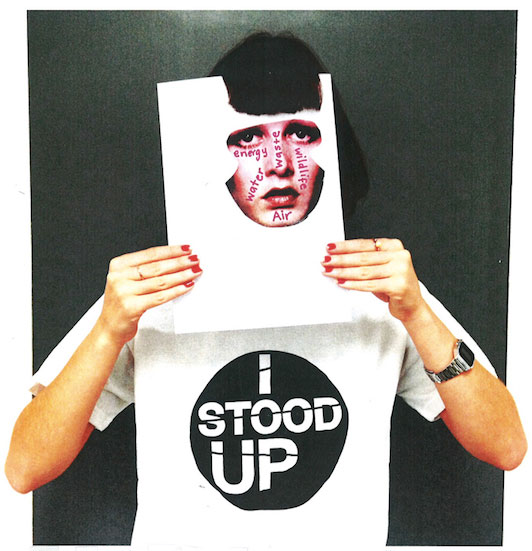

Fashion can make us individually vulnerable; we put out into the world an idea for public viewing and scrutiny, it’s written all over our bodies. We create statements and commitments through our spending (time, money, skills, attention) on things that name us, identify us as distinct or similar to others. We take a punt on how we’ll be received in a social world and how we’ll feel about ourselves. This risk-taking can offer vitality or fragility. It can make us collectively vulnerable too, its practices and artifacts often relying on scarce resources, the drawing from which compromises nature and society’s balance. Can this collective vulnerability become a means to energize social resilience in its wake?

Fashion can make us individually strong; we create affirming, adaptable, diverse, meaningful and usually voluntary actions through our attire. We create and follow habits and rituals that relate to vital elements of being human in the world. This position can embolden us, but it can also distance us through a notion power and hierarchy. It can make us collectively strong, its practices engaging millions of people (mainly women) in gainful employment through the making of its collateral: the human energies and activities, materials, services, economies, communities and the communication that it entails. Yet this strength is built on industrial practices that tend to fix components in a regulated manner, at odds with the undulating nature of life and all that it thrives on.

‘The relationships, actions and endeavors that are mediated through the creation, wearing and caring for our attire form narratives of what we make of being human, in our place and time.’

Millions of citizens practice a democratic right through their visible and undercover fashion practices, which can be playful, political and personal. Fashion’s role is visible in every day activities in our cities, towns, fields and farms, it is profiled in newspapers, through social media, in fashion capitals and raved about as an economic generator by governments the world over. It also finds root at the edges of our vision, informal city practices generating emergent properties giving place and form to cultures and societies. It is not fixed, just as sustainable fashion is not a static term. The relationships, actions and endeavors that are mediated through the creation, wearing and caring for our attire form narratives of what we make of being human, in our place and time. It is part of our endeavor to ‘do what we can’, as individuals and as a social species. Creating a culture that is hospitable to all manner of activities, necessitates, a common value, a sense of justice that is not just about the right way to distribute things, but also about the right way to value things (Sandel 2010). The elastic connection between assertion of individuality, connectivity within community and wider contribution to societal infrastructures is a yarn that might be spun through looping fashion as personal and social ‘making’.

The Nature of This Flower Is to Bloom

And for ourselves, the intrinsic Purpose is to reach, and to remember, and to declare our commitment to all the living, without deceit, and without fear, and without reservation. We do what we can. And by doing it, we keep ourselves trusting, which is to say, vulnerable, and more than that, what can anyone ask?

June Jordan, in a personal letter, 1970, Alice Walker, ‘Revolutionary Petunias’

Hospitable cultures of resilience thrive on curiosity between consumption and conceptions of value, the immediate and the anticipated, the near and the distant. Locations for such cultures might be usefully explored in the conviviality within the geographical domain of our cities, an increasingly dominant home for a majority of citizens. It is anticipated that by 2050, in this age of the Anthropocene, 75–80% of the world’s people will be located in cities, their contribution to or draining from nature, and humanity will be affected by the cultures of resilience that they can generate. Whilst much city growth is taking place in the global south, social as well as environmental conditions in London offer an apt place for experimentation. London hosts 270 ethnic groups, speaking 300 different languages and expected dramatic changes in the city include wide climate fluctuations, changes in resource availability and economic uncertainties. The resilience of London depends on its ability to anticipate, dissolve and adapt to crises rising from demands of its citizens. London is home for a great diversity of both formal and informal fashion practices, a tradition in design, making and parading of fashion identities, as well as a platform for global fashion manufacturing and distribution.

‘The elastic connection between assertion of individuality, connectivity within community and wider contribution to societal infrastructures is a yarn that might be spun through looping fashion as personal and social “making”.’

Starting ‘where we are’ might enable us to participate in an exploration of the city’s social energy, to look at how city making and fashion making might link together. City making, just as fashion making, represents extremes in vulnerability and strength, often in close proximity. We are brought together by our ‘concerns,’ of which shelter, food and fashion are paramount. Intertwined amongst these, we find love, safety, death, health, nature, friendship, recognition, fulfillment, equality, democracy and voice. For these ‘concerns’ to find form, we need to create conditions for commitment and consensual involvement on an individual and collective level. The skills that we need as ‘hosts’ to these conditions are the skills that might equip us to become 4D facilitators of convivial lifestyles.

As humans, we do not by nature set out to harm, cause strife or suffering, as evidenced both biologically in the empathy gene (Rifkin 2010) as well as societally in the many ways that family, friends and communities’ contribute to healthy ecosystems. We do, however, all want to make our mark. This balance between collaboration and competition occurs across nature, including between people and within nature. When in balance, there is a flow between collaboration and competition that creates a striving for success, but not at the expense of others, ie a common good or citizen ethic. So, taking a cue from David Orr (1991), ’…think of yourselves first as place makers, not merely form makers. The difference is crucial. Form making puts a premium on artistry and sometimes merely fashion. It is mostly indifferent to human and ecological costs incurred elsewhere. The first rule of place making, … is to honor and preserve other places, however remote in space and culture. When you become accomplished designers, of course, you will have mastered the integration of both making places and making them beautiful.’

In doing so, we expand notions of fashion back towards their origins of ‘bringing together to make with style’ and forward to ‘embrace the chaos of an uncertain future.