Managing chaos not cleaning up mess

Melanie Dodd

One of the most disturbing aspects of dialogues about sustainability (particularly in the field of architecture and urbanism) is the absence of culture from any part of the definition. When people talk about sustainability in architecture and the built environment they most often frame it around an instrumentally driven approach, which privileges measurable technical outcomes and building performance values to the exclusion of broader social and cultural complexities. The culture deficit has been particularly evident in a lack of understanding about, and a disregard for the way networks of cultural production, specifically creativity, can promote and engender effective and alternate ways of living in cities, as evidenced in the way that artists are critical to cycles of innovation (Oakley, Sperry, Pratt, 2008).

Furthermore, cities are places of diversity, complexity and difference; ecosystems of barely balanced chaos and flux. Necessarily, policy decisions control cities at the level of the meta-narrative, but are often too imprecise to nurture the small-scale, disruptive but necessary differences between different spaces, cultures and areas. We need to value the ‘imperfect’ aspects of urbanity and formulate a way forward to manage adaptation and adjustment over time; a matter of managing the chaos rather than cleaning up the mess.

How might we foreground more marginalized cultural and creative practices in cities and acknowledge the way they (provocatively) re-conceptualize and sustain our contemporary lives?

‘Necessarily, policy decisions control cities at the level of the meta-narrative, but are often too imprecise to nurture the small-scale, disruptive but necessary differences between different spaces, cultures and areas.’

How might a creative practice of ‘managing the chaos’ be conceived and undertaken, and what examples can we identify that might help us? Ideas about creativity in the city are not new. In the past twenty years there has been a significant upsurge in writings and debates about the notion of creativity, creative clusters and the creative city ‘but as these terms have filtered through to the popular media they have lost their precision and specificity and collapsed into more or less the same generic or bland idea’ (Pratt, 2010). His comments point to a growing acknowledgement of the need to move beyond overly broad and generic justifications for the ‘creative city’ and creative economies within cities. As Pratt says, we need to recognize the ‘value of acknowledging the subtleties of historical and locally specific practices of cultural and creative activities; only by taking such an analytic step can we understand the processes animating creative cities, and accordingly begin to develop a range of policy responses to them’.

There are serious problems associated with a lack of detailed analysis on local and specific examples of cultural and creative activities in cities. This has resulted in imprecise interpretations of how creative clusters form, and are sustained. Worryingly, the role of policy driven culture and creative industry-led renewal and regeneration has often resulted in the raising of property values and rents, attracting cultural consumption and promoting city living, such that gentrification arguably discredits the notion of creativity and at worst, connects it to problems of social inequality. An understanding of the threats to, and from, creative clusters, and further research on the way that (actually) locally specific practices of cultural and creative activities can resist the forces of gentrification, is therefore critical to their sustainability. Central to opening up this research, and to return to our question, we need to focus on the way small-scale creative and cultural practices ‘manage the chaos’. Interestingly, it has been found that the influence of key individuals, whether entrepreneurs, family businesses, or artists, are often required to first create and then sustain local networks and facilities. This is especially the case with smaller artist and designer studio organizations and larger community arts organizations, which are critical in the way they provide ongoing and practical advocacy for artists and creative users (Evans, 2011). Perhaps we might call this a type of ‘creative agency’ where we define ‘creative agency’ as the capacity to enable others to act creatively in the world, and also the capacity for that agency to enable engagement in broader cycles of cultural production. How does such creative agency (necessarily messy, idiosyncratic and disruptive) operate successfully to sustain cultural production and creative activities, and is the key their particular (small) scale of operation and inherent flexibility?

In the case of arts organizations, creative agency can range from enabling practical aspects of how an artist acts, produces and consumes objects including in space (rooms, studios, galleries, the city) over time (tenancies, residencies, tenures, exhibitions, events), and in specific locations (market, locale, historical and cultural territory) to more ephemeral, enabling, or indirect capacities such as educational support, financial support, and the social and cultural structures and frameworks which encourage and drive creative productivity, and facilitate the intrinsic and instrumental values of its production to be accessible the rest of society. Considering these definitions of creative agency, and cultural production as forming a complex ‘matrix’ or web of interactivities and enchainment, how can we unpack the constituent parts of the ingredients of the matrix to provide a clearer and more lucid picture – a picture which can acknowledge and illustrate the subtleties of locally specific practices of cultural and creative agency?

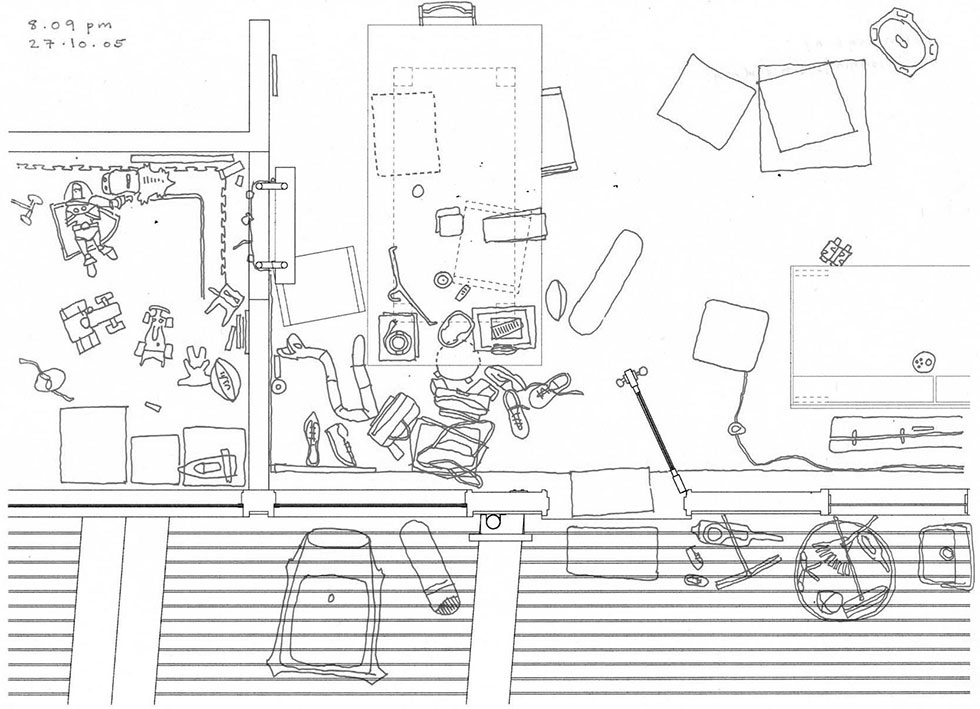

For me one critical hurdle lies in how we might represent, make legible, and so understand the constituent components of such a matrix. Since there are both strongly geographic and proximate qualities to artist’s enclaves, alongside virtual and ephemeral networks of social connection, the ‘management’ of the matrices operates across both the tangible sites of the city, as well as the intangible. The multiple modes of creative agency in the city (spatial, cultural, social and economic) are difficult to communicate through conventional empirical tools and mechanisms commonly adopted by the policy-maker. We need hybrid representations of other values that extend beyond the metric alone, capturing a wider range of scales and qualities, from the local and spatial to the global and virtual.

‘The value of “managing the chaos” of creativity in cities might best operate at this micro, or mid scale, and present an alternative to the ‘meta’ scale narrative and the blunt tool of policy.’

The creative agency of small to medium-scale cultural organization underpins the literature on creative production in cities, since their effects are to engender and sustain creative clusters. But as the ‘idea’ of creativity has been co-opted and instrumentalized in urban redevelopment narratives, the operative and detail know-how of their creative agency has been successively devalued, if indeed it was ever properly understood in the first place. Yet ironically, it is probably clear that the value of ‘managing the chaos’ of creativity in cities might best operate at this micro, or mid scale, and present an alternative to the ‘meta’ scale narrative and the blunt tool of policy. Having a better understanding of the complex web of interactions – the actual creative agency – inherent in these organizational operations, is a key to respecting and valuing what they do, and a critical step on the journey towards reproducing it at a wider scale for the benefit of everyone living in cities.1Oakley, Sperry, Pratt (2008). The Art of Innovation: How Fine Art Graduates contribute to Innovation, NESTA.2Pratt (2010). Creative cities: Tensions within and between social, cultural and economic development, A critical reading of the UK experience, City, Culture and Society 1 (1), pp. 13–20.3Nathan, M (2005). The Wrong Stuff, Creative Class theory, diversity and city performance, London: IPPR.4Montgomery, J (2005). Beware the Creative Class. Creativity and Wealth Revisited, Local Economy 20(4), pp. 337–343.5Peck, J (2005). Struggling with the Creative Class, International Journal of Urban and Regional Research 29(4), pp. 740–770.

References

| 1. | ↑ | Oakley, Sperry, Pratt (2008). The Art of Innovation: How Fine Art Graduates contribute to Innovation, NESTA. |

| 2. | ↑ | Pratt (2010). Creative cities: Tensions within and between social, cultural and economic development, A critical reading of the UK experience, City, Culture and Society 1 (1), pp. 13–20. |

| 3. | ↑ | Nathan, M (2005). The Wrong Stuff, Creative Class theory, diversity and city performance, London: IPPR. |

| 4. | ↑ | Montgomery, J (2005). Beware the Creative Class. Creativity and Wealth Revisited, Local Economy 20(4), pp. 337–343. |

| 5. | ↑ | Peck, J (2005). Struggling with the Creative Class, International Journal of Urban and Regional Research 29(4), pp. 740–770. |