AN OPPORTUNITY TO EXPLORE FASHION AS PARTICIPATORY DESIGN IN A CITY LOCALE

DILYS WILLIAMS AND RENEE CUOCO

In November 2015, we hosted a pop-up event, I Stood Up for (Bio)diversity, in a vacant shoe store at Chrisp Street Market in Poplar, East London. We transformed the empty space for one day to share findings from the Habit(AT) research project and facilitate conversation with the local community through fashion and participatory design activities. Whilst our initial findings, garnered from 140 participants, are not generalizable, they suggest that such processes and practices might reveal, amplify or even create the conditions for place-based social forms, re-enforced by their visibility as spectacles of fashion in the city. Through this feedback loop, an ethos rises up, is made visible (spectacle), becomes accepted (norm), and evolves. Thus the balance between matter making and meaning making might be restored.

Recognition was given to the fact that the raw format evoked at Chrisp Street requires the ‘professional participants’ (researchers and MA students) to be open, vulnerable and exposed, as participants in, rather than leaders of a design process. Whilst not common practice, open-ended participatory design is increasing in visibility across art and design disciplines, Marina Abramovich’s 2015 exhibition, 512 hours, being a case in point. It beholds the socially and ecologically engaged designer to create conditions where ‘every human being participates in the creation of a world experienced as a multiverse of diverse others’ for ‘a relational dynamic to be truly felt.’ In this case ‘the professional designer need not be suppressed, but needs to be redefined as a facilitator of socio-ecological processes’ (Cross 2006).

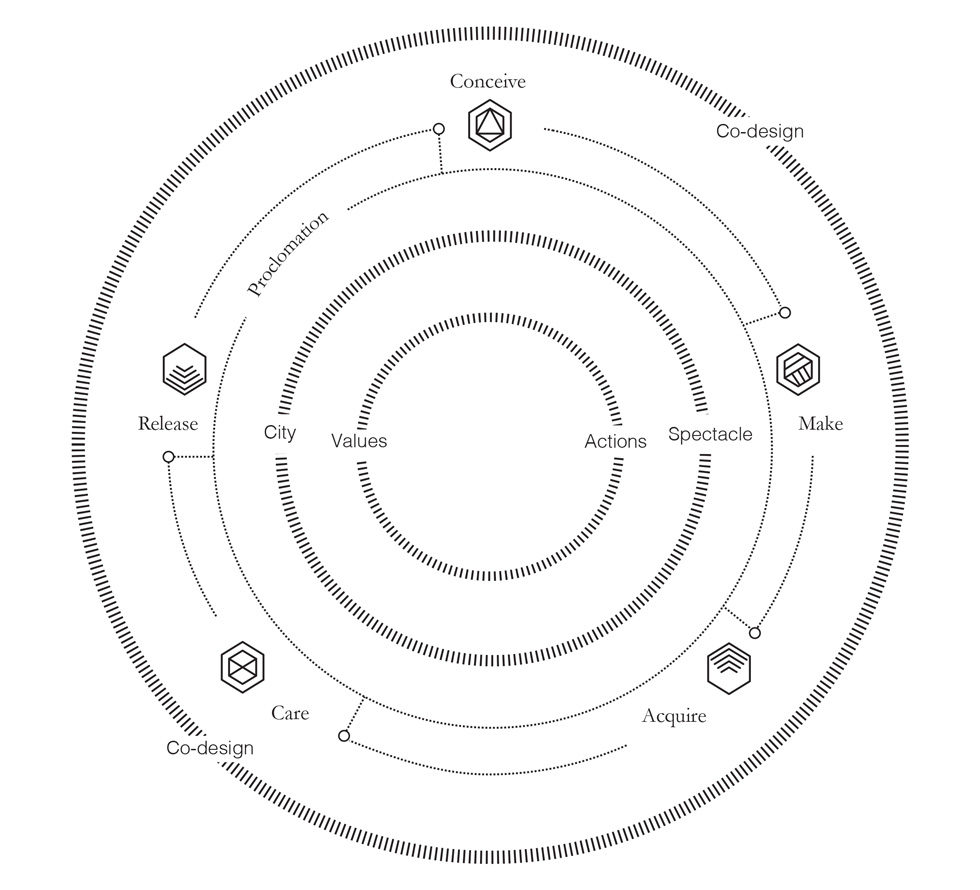

Through strolling and noticing to explore fashion forms, events and exchanges in the small surrounding area of Chrisp Street, we could begin to understand the elements that come together to create the spectacle. By noticing the interactions of people, place and fashion, we found two ways in which fashion facilitates the forming and proclaiming of a city’s culture, and manifests its social and material flows:

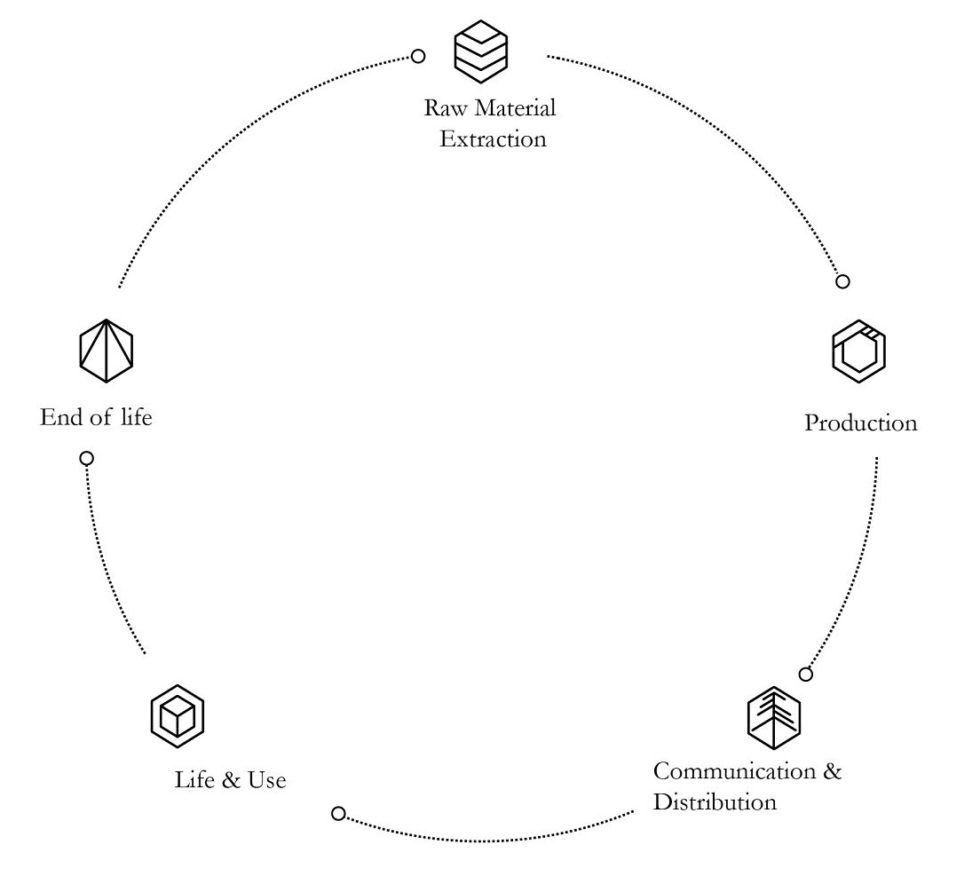

- Elements of action (described below), which form alternative fashion narratives to the commonly described lifecycle analysis. These are not independent, nor complete, rather they connect people and resources in interrelated flows, their movements sometimes overlapping personal and social interactions, where fashion is practice, garment and statement.

- Proclamation, which may be loud or quiet, refers to visible manifestations of self in a place. Fashion comes to life on the body, realizing its practical aspects of protection, modesty and ergonomic function, but maybe more critically, its social role in declaring a sense of ‘being human’ in the world. The wearing of fashion in this regard is a political as well as practical endeavor, a demonstrating of the individual and their agency in a place.

ELEMENTS OF ACTION

- Conceive: visible traces of places and interactions where ideas are born and seeded (designer’s studio, fabric stall, social space).

- Make: visible traces of the making of fashion (factory, studio, sewing group, community centre).

- Acquire: visible traces of acquiring, gaining, buying, borrowing, selling, exchanging or learning of fashion (stores, market-stalls, waste skips).

- Care: visible traces of the caring for and about fashion (laundromat, dry cleaners, tailors, haberdashery store).

- Retire: visible traces of the discarding, gifting or re-acquiring of pieces of fashion (charity shop, recycling point, bin, car-boot sale).

The individual demonstrations of concern facilitated through fashion, as explored at Chrisp Street, do not sit neatly alongside fashion’s elements of action, but rather weave in and out of all aspects of the city’s social forms. By witnessing members of the public stand up in a piece designed to relate to their location, and to share concerns in response to visual and oral prompts, confirms to us that each one of us makes meaning through what we wear, alongside and sometimes as part of fashion making and caring. The verbal responses and photographs of participants that were gathered present themselves as a series of articulations of the city, collectively creating a spectacle of fashion that can act as an alternative to those usually reported as ‘fashion in the city’.

In the highly structured setting of fashion in many cities, globally reported fashion weeks and gigantic retail emporia mean that the spectacle of fashion is often fixed; sellers display, shoppers buy, and the currency of a brand can determine the city’s reported style and accepted practices. The economic arrangements at play here, their social divisions, underpinned by political systems and influenced by the acceptance of the city’s inhabitants, lead to forms and events that endorse the city’s often precarious practices and related identity.

As evidenced at Chrisp Street, there are however, other, more fluid, less hierarchical settings for fashion spectacles in the city; often under reported, but nevertheless offering the chance (in our experience quite easily), to visualize new and established cultures of resilience. Markets, historically the meeting place for public activities and the exchange of locally related goods and services, ‘a social structure for the exchange of rights’ (Aspers 2013), can offer a means for professional and citizen designers (Cross 2006) to create social and material forms and ties that multiply restorative practices as they become more visibly part of a city’s ethos and identity. Whilst many markets are now locations for the exchange of goods created many miles away, the visible, tangible sense of everyday personal lives and livelihoods intertwining in a market environment, often mixing old and new, eclectic choice over retail dictation, are spaces for fashion as social connection as well as commercial exchange.

The city is ‘an instrument for understanding the world and the human predicament in it’, (Rykwert 2013), but if we substitute ‘city’ for ‘fashion’ we see a new way to view fashion that connects social processes of fashion-making and city-making as identifiable and highly visible forms of culture. Fashion design, in creating social and material forms, is distinguished as meaning as well as matter making. The former, however, is seldom foregrounded in the discourse of fashion and sustainability, where a rational approach is usually taken, with tools such as lifecycle analysis averaging out existence into a predictable, consistent and managed process (see diagram 1 and 2). But the world and fashion are not like that; how we live and how we wear cannot be prescribed or known as absolutes. The social fit of our clothes involves more intuitive, personal stories and knowledge, which are less easily transferable (Reid 2013), and yet, it is these elements of fashion that stich a city’s social forms and visual narratives together, connecting matter with meaning. Subjective experiences, rather than known fact, involve ways of knowing that are ‘narrative unity and practice’, (Walker 2014), evolving not only through our own developing sense of self, but through the relationships and influences that we have on each other and through ‘the elastic connection between assertion of individuality, connectivity within community and wider contribution to societal infrastructures.’ (Williams 2015).

Through our work at Chrisp Street we recognised the value in exploring the city as a location of spectacle, where people and place, form and event, come together to visualize a city’s culture, ethos and habits. Actions and proclamations of the fashion-spectacle were made visible with local citizens in Chrisp Street Market, and we can see the spectacle of a city created through the activities of its people in relation to the physicality of its space; fashion playing a definitive part. The spectacle is a means to create the habitus, socialized norms that guide behavior and thinking (Bourdieu 1984). The ways in which society becomes deposited in people in the form of lasting dispositions, propensities to think, feel, act in determinant ways, (Navarro 2006: 16), is a reciprocal process informed by the visibility of citizen actions. It is clear fashion is both part of the creation of the habitus, and part of its evolution.

References

| 1. | ↑ | Abramovich, M. (2015). 512 Hours. Exhibition. Information available online at http://www.serpentinegalleries.org/exhibitions-events/marina-abramovic-512-hours |

| 2. | ↑ | Aspers, P. (2013). The Handbook of Fashion Studies. Bloomsbury. |

| 3. | ↑ | Being Human Festival. Information available online at www.beinghumanfestival.org |

| 4. | ↑ | Bourdieu, P. (1984). Distinction: A Social Critique of the Judgement of Taste. London, Routledge. |

| 5. | ↑ | Corby, T., Williams, D., et al. (2016). I Stood Up: Social Design in Practice. Art and Design Review (ADR) Vol.4 No.2 2016. Available online at http://www.scirp.org/journal/ADR/. |

| 6. | ↑ | Cross, N. (2006). Designerly Ways of Knowing. Springer-Verlag London. |

| 7. | ↑ | Navarro, Z. (2006). In Search of Cultural Interpretation of Power. IDS Bulletin 37(6) pp.11-22. |

| 8. | ↑ | Reid, K. (2013). From fragmentation to wholeness. Resurgence and Ecologist. The Resurgence Trust, Devon, UK. July/August, No.279 pp.32–35. |

| 9. | ↑ | Rykwert, J. (2013). The Idea of a Town: The Anthropology of Urban Form in Rome, Italy and the Ancient World. Faber and Faber main edition (first published 1963). |

| 10. | ↑ | Walker, S. (2014). A narrowing of meaning: loss of narrative unity and the nature of design change. International Journal of Sustainable Design Vol.2 No.4 pp.283-296. |

| 11. | ↑ | Williams, D. (2015). Cultures of Resilience Ideas Book. Available online at http://www.arts.ac.uk/research/ual-university-chairs/event-archive/cultures-of-resilience/cultures-of-resilience-ideas-book/ |